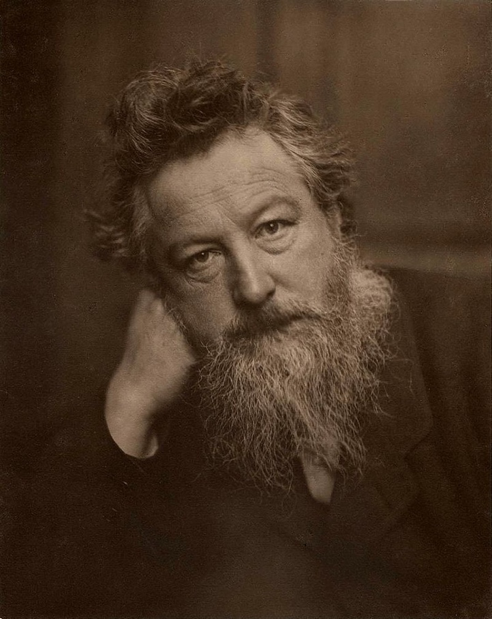

William Morris

Photographic portrait of William Morris (UC Library)

As many young students return back to Oxford for the start of their new academic year – or arrive for the first time – we take a look at one artist who also took the same path…

William Morris (1834-1896) is widely known as a multi talented figure who was not only a British textile designer, but also a poet and socialist reformer. He reacted passionately against what he viewed as the debased culture of machinery brought about by the rise in Industrialisation and was opposed to the manufacturing processes and the mechanical development of art and works in factories.

To him, the ornament or artwork itself was losing meaning as a result of the Industrial Revolution, which was beginning to replace the originality or ‘aura’ within art. Inventions such as the camera could reproduce images over and over again with the resulting artwork losing its individuality, personality and ability to tell a unique story.

Detail of Fruit Wallpaper designed by William Morris, 1865-66

Morris began his academic education at Oxford University, studying Theology. Here he met fellow friends and long life collaborators William Fulford, Richard Watson Dixon, Charles Faulkner, Cormell Price and his closest friend, Edward Burne-Jones. In the summer of 1855, Morris and Burne-Jones went to France to see the Gothic cathedrals. Inspired by what they saw, they decided that their future path was not in fact to be a pious one, but was instead rooted within art and all things creative. They had become disillusioned with the methodologies of the church, but were completely enchanted by the dazzling interiors and decorations inside them.

It was in London where the two encountered the ‘Brotherhood’ or the ‘Pre-Raphaelites’. A major art group at the time, it was formed by Royal Academy students Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. They were all influenced by the writings of John Ruskin, a strong advocate of the handmade in contrast to the mechanical. With a passion and vigour akin to that which inspired artists of a preceding period in admiration of Roman and Greek arts, they wished to revive the glories of the medieval and vernacular arts. The Brotherhood sought to create art that reimagined the romanticism of the Medieval period, but also the period before the great Raphael, with the use of bright colours and a close analysis of nature. These ideals appealed to those held by the younger Morris.

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (The Annunciation) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, oil on canvas 1849-50

Proserpine by Rossetti (Jane Burden is the model, a muse for many of the Pre-Raphaelites and also the wife of Morris) Oil on canvas 1874

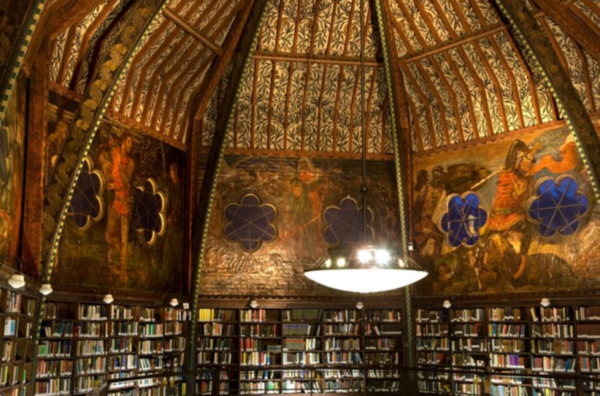

Morris intended to become an architect and started as an apprentice in an architecture firm whilst Burne-Jones was apprenticed to Rossetti. When Rossetti met Morris he persuaded him to focus on creating art instead and invited the pair help him with a commission to paint a series of murals in the new Oxford Union debating chamber.He asked many other artist friends to join as well. They painted tales from the Arthurian legend, which was never fully finished.

The Pre-Raphaelite murals in the Old Library at the Oxford Union were painted between 1857 and 1859 by a team of young artists including Rossetti, Morris and Burne-Jones. The paintings depict scenes from the Arthurian legends. The ceiling design is by Morris. (Oxford Union)

Later on in life, Morris copiously studied traditional methods of dyeing that used natural dyes, which he believed produced an intensity of colour unprecedented in chemical dyes on the market. He became very knowledgeable on the subject, and experimented with older techniques of dyeing with indigo, madder and other natural colours. He wrote an essay on his findings entitled ‘The Art of Dyeing’ so others could share what he had learnt. He also taught himself to weave by following instructions on a printed manual and in a short time he was able to produce complex technical structures.

Sunflower ceramic tile in the William Morris Gallery Collection, 1870s

Diagonal leaf ceramic tile in the William Morris Gallery collection, 1870s

In 1861 he set up the design firm Morris & Co in partnership with Rossetti, Burne-Jones and four other friends. The firm created all manner of beautiful handmade crafts including ‘multipurpose interior decoration murals, carvings, glass, metalwork, jewellery, furniture and embroidery’ as well as stained glass window design. In some ways, Morris did embrace new technologies in printing, so he could make reproductions of his designs. His political beliefs were apparent in his feelings toward art. He stood for democracy in art, and therefore that everyone could have access to it. By making so many reproductions this was one way to achieve that.

In his book Nowhere, Morris relays his feeling that art is not just a pretty picture on the wall, but ‘in the the detail of everyday life’.

Honeycomb woven wool textile, designed 1876. (William Morris Gallery Collection)