Stained Glass Windows: Radiant Light and Colour

Radiant, delicate and bejewelled: Sainte Chapelle in Paris (1239-1248). Commissioned by Louis IX to house his collection of religious relics. A wonderful example of the Rayonnant style of Gothic architecture with fifteen massive stained glass windows of fifteen metres high.

It may be hard to imagine now but stained glass was at one time considered and respected as a form of painting. It was not only a way to decorate church interiors, but also used to tell stories and to emotionally engage with people.

The way stained glass has historically been made has not changed much today. The artist first produces a ‘cartoon’, an initial sketch of the desired pattern. Irregularly shaped pieces of coloured glass are then joined with lead to replicate the sketch and details are later refined with a fine brush. The colours of glass were determined by glassblowers who included various metal oxides to the molten glass, producing definite hues in the finished sheets.

The technique of glassblowing is age-old. Discoveries of the process eventually spread throughout the world, however during the Middle Ages, Venice was a major centre for glassmaking and glassblowing. The masters of this art were eventually moved from Venice to the island of Murano, in order to avoid potential fires spreading within the city but also to keep their knowledge and techniques a secret…

Whilst stained glass windows could encapsulate visual stories in the same way as paintings, unlike images on canvas, the narratives on glass were illuminated by natural light pouring through them, amplifying their message and their monumental effect on visitors.

The importance of stained glass windows flourished in France during the birth of the Gothic period in architecture, an era that was characterised by taller, thinner structures that were intended to appear lighter, primarily achieved by extensive use of stained glass windows.

Stained glass windows in Saint Denis in France, 12th century.

Saint Denis Church in Paris is considered one of the first examples of the Gothic style and has many stained glass windows, with special significance placed on the colour blue. The supervisor of the architecture, Abbot Suger, extolled the colour blue as divine and believed that incorporating it into stained glass would induce a metaphysical experience in the viewer. Suger apparently provided the most expensive sapphire glass for the windows’ design, akin to the jewel-like sparkle of gemstones. The natural light from outside that passed through the coloured blue stained glass was intended to dazzle the viewer into witnessing a transformed, spiritual light.

Abbot Suger believed sensory impressions derived from bright colours drew the onlooker ‘from the material to the immaterial’, bringing the divine into human life.

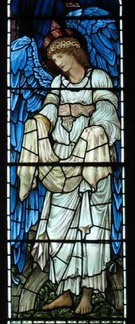

In the nineteenth century there was a desire to revive beauty within art. Artists looked back to the Medieval period for their intricate, awe inspiring way of making, being particularly inspired by their stained glass windows. These had a handmade quality that somehow became lost in the Victorian era of industrialisation and commercialism. In Oxford, this resurgence was spurred by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who were greatly inspired by medieval themes. The key patron of this group, the art critic and artist John Ruskin had studied himself at Christ Church college in Oxford. This is the only college that has a cathedral instead of chapel, and within it are stained glass windows designed by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones. Inspired by Medieval illuminated manuscripts, Jones made use of wonderful, rich colours.

Detail of Edward Burne Jones’ stained glass at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.

“Blue colour is everlastingly appointed by the deity to be a source of delight.” John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1866

There are, in fact, many contemporary artists who created paintings both on canvas and on stained glass. A few more notable examples are Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Marc Chagall and Fernard Leger.

Marc Chagall’s ‘America Windows’ from the exhibition at The Art Institute of Chicago, 2010-2011.

Towards the end of his life, Henri Matisse worked towards designing the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, in the South of France. It was created primarily for the Dominican sisters who had looked after him in hospital and particularly as a token of gratitude for his nurse Monique Bourgeois. The chapel was emotionally significant to the artist who felt through this work, he had achieved a sense of radiant light and colour that he had dreamed of as a child. It was his masterpiece.

Matisse created the stained glass windows inside as well as ceramic murals and a blue and white pattern on the roof of the chapel. The windows are made up of ultramarine blue and yellow, comprising of natural leaf and geometric patterns in his notorious ‘cut-out’ style. Matisse told his grandson that what pleased him the most was the intensity of the clear blue in the chapel, that he had seen before only in the “glint of a butterfly’s wing, and in the pure blue flame of burning sulphur.” And added that…”Pure colours… have in themselves, independently of the objects they serve to express, a significant action on the feelings of those who look at them… Simple colours can act upon the inner feelings with ore force, the simpler they are. A blue for example accompanied by the brilliance of its complimentaries, acts upon the feelings like an energetic blow on a gong.” Henri Matisse

Interior of Matisse’s Chapel in Vence, France, 1948-1952.

“A blue…accompanied by the brilliance of its complimentaries, acts upon the feelings like an energetic blow on a gong.” Henri Matisse

The German designer Johannes Schreiter created specifically white and blue stained glass windows for some churches in Germany. Blue was chosen as the predominant colour for many of his geometric windows for his belief in its ability to create an atmosphere of tranquillity and to suggest sense of infinity and the ‘beyond’, much like Yves Klein’s thoughts on the colour.

Window in Sacraments Chapel, Essen Munster, Germany.

Vivid blue stained glass window designed by George Braque in the church at Varengeville-sur-Mer in Normandy, France where he is buried.

It seems that both Medieval and contemporary stained glass artists intended their windows to emotionally move and inspire visitors. Like Matisse said, he wanted visitors upon ‘entering the chapel to feel themselves purified and lightened of their burdens’. To many, blue was seen as the supreme colour for stained glass due to a belief in its divine and spiritual qualities.

Yet, whether religious or not, the light coming through these windows would bathe people in bold and vibrant colour reflections, from light streaming through the colourful glass onto the bodies of the viewer and the interior of the building, offering a moment of calm within the hurly burly of life…or the hurly burly of Christmas preparations!

John Piper’s stained glass window in St Mary’s Church in Turville, Buckinghamshire from 1975. “Ever since I was taken to Canterbury Cathedral as a child, my heart beats faster when I see blue glass in church window.” John Piper