Drenched in the Light of Sargent

John Singer Sargent was born in Florence in 1856 and spent much of his childhood travelling around Europe with his family, to Italy, France, Spain, Germany and England, soaking up different cultures. John’s mother, Mary Newbold Singer, was a watercolourist and recognizing her son’s enthusiasm for observational drawing, encouraged him to pursue art. It soon became clear that his future path was as an artist and he went on to study at prestigious schools in Florence and then later in Paris. He entered the studio of Charles Carolus-Duran, a famous portrait painter in Paris, who had unconventional methods for the time, telling his students to paint immediately rather than making preparatory drawings first, and to paint what they saw in tonal modelling. This helped Sargent really observe nature and meant he was very able to conjure up form with a few brushstrokes.

In the late 1870s Sargent saw the work of the Impressionists in Paris and was particularly attracted to Monet’s works, later becoming friends with the artist. Although Sargent would have studied the traditional techniques of the Old Masters, he stretched the limits of convention and injected vibrant colour into everyday scenes, much like the Impressionists. Akin to them, he also concentrated on the evanescent, spontaneous moment and the effects of light outdoors. Although Sargent was well known for his portraits of high society, he also created joyful, scenes en plein air in which he often used blue and white together.

Filet et Barque (Net and Boat) 1889, watercolour on paper

Sargent was a wonderful watercolourist. His fascination with capturing a fleeting moment seemed to work with the immediacy and speed that watercolour allowed for as a medium, and of course it was fitting for his depictions of water, as in Filet et Barque. Here, it’s almost as if we can hear the boat gently lapping on the ripples of water, which are rendered in many different nuanced shades of blue. The edges of the net with dark red and white balls, looks like fairy lights glistening in the twilight. Sargent breathes life and poetry into an otherwise mundane scene, making us want to look at it for longer and relax into the scene.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose 1886, oil on canvas

Sargent’s masterpiece is undoubtedly Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, which hangs in Tate Britain and is the painting which gained him a reputation as the preeminent “British Impressionist”, a legacy still cherished by many today. This is a twilight scene in summer, of two young English girls in white dresses hanging paper lanterns in a beautiful garden of Japanese lilies and carnations. He was inspired by Chinese lanterns he saw hanging among trees, on a Thames river trip, at Pangbourne.

He started the painting in 1885, taking two summers to complete it as, tantalisingly, he was only able to work for a few minutes each evening when the light was exactly right; when yellow candlelight just outshines purplish daylight. The way he painted was very physical, people commented that he was like a fencer. He had to work quickly because of the light, trying desperately to transcribe what he could see before his eyes onto the canvas. Some of Sargent’s contemporaries would have considered this painting to be unfinished due to his gestural brushwork, and indeed he did get mixed reviews when it was exhibited. However, his sweeping brushstrokes animate the scene and give it a sense of movement, as in the way pink-orange strokes in the ridges of the white lanterns suggest the internal warm illumination in amongst blue shadows.

This painting speaks to us on an emotional level, with its subject of innocence and childhood, but also invites a gentle sensory viewing experience due to the quality of light depicted and the colour harmonies within the painting. This was one of the key paintings which spurred the Aesthetic movement that developed in Britain, advocating ‘art for art’s sake’, advocating the visual poetry and beauty of art rather than moral and narrative concerns which had previously been the primary focus of art.

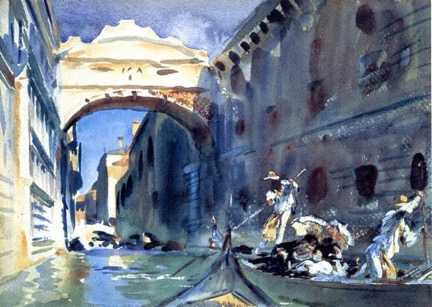

The Bridge of Sighs, c. 1903-1904, watercolour on paper

One of Sargent’s favourite places to paint was Venice, a place he knew well from his travels as a child. He delighted in the light there as well as the water, architecture and boats, returning year after year. We may think of watercolours typically as being subdued in colour, but Sargent proved this wrong with his vibrant, bold works. He liked to sketch and paint whilst sitting in a gondola. In The Bridge of Sighs, the artist paints a lively scene on the water looking up at the bridge, one of Venice’s most famous structures, through which prisoners were transferred from the prisons to the Doge’s Palace. Prisoners were said to have sighed on their way to execution. However Sargent does not focus on this dismal history, instead he illustrates the interplay of light and dark primarily with a dual palette of blue and white. He applies white impasto to areas of the figures on the boat and focuses on different shades of blue for the shadow and the sky. Sargent painted on dry paper and often left areas of the white paper he worked on bare so as to suggest highlighted, more sun drenched areas like the top of the bridge.

Rio dell Angelo 1902, watercolour on paper

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Sargent became one of the leading and most sought after portrait painters of his time, painting the likes of Theodore Roosevelt, John D Rockefeller and Henry James. His works are treasured today internationally for his ability to express the essence of his times, breaking from the Old Master tradition toward an Impressionist style yet always maintaining a unique and independent vision, always infusing his canvases with sentiment, energy and life.

A Morning Walk, 1888, oil on canvas. Here we see Sargent looking towards Monet (as well as perhaps Renoir) who painted similar portraits of his stepdaughter also wearing white and carrying a parasol in the open air. Sargent spent some time in Oxfordshire and it is believed that this was painted there. This portrait shows an elegantly dressed woman strolling along the edge of a stream.