Defining Techniques: Pointillism

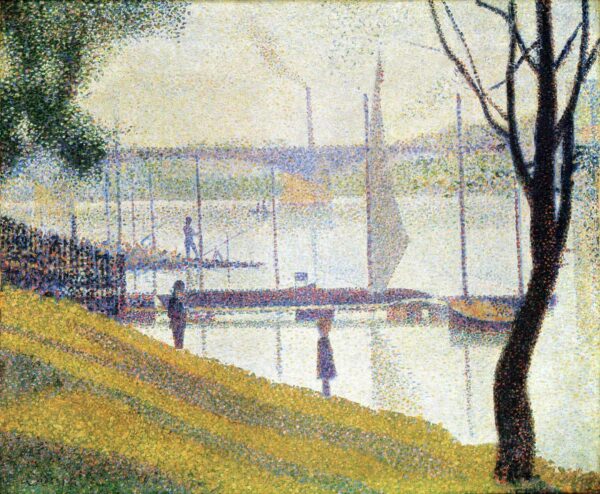

Georges Seurat, Bridge at Courbevoir, 1886-1887, Oil on Canvas

One of the greatest joys of studying the history of art is getting to learn about the evolution of art movements over time, and the techniques which often played a part in defining them.

A significant moment in that evolution can be recognised in the late 1700s to early 1800s, during which time the academic ideals of painting were beginning to be questioned. This came hand in hand with the invention of the camera and, thus, we saw the dawn of modern art.

Pointillism was an amalgamation of the new avant-garde approaches that blossomed in this timeframe. Combined with scientific theory, it resulted in both delightful land and seascapes as well as fascinating depictions of modern life in Paris.

The fundamental Pointillist intention of achieving beauty through colour is something which we obviously resonate with strongly here at Blue & White Company . Therefore, we thought we would explore the technique and have a look at where the colour blue might have also played a starring role.

What is Pointillism

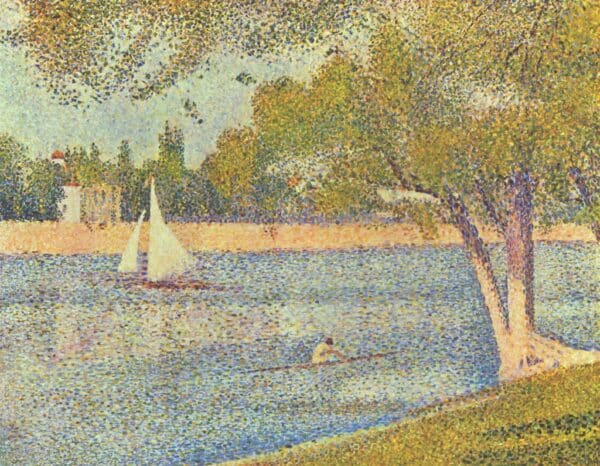

Georges Seurat, The Seine at La Grande Jatte, 1888, Oil on Canvas

Pointillism is the name frequently given to the Neo-Impressionist technique developed by the artists Georges Seurat and then Paul Signac in the late 19th century. As artists such as Cezanne and Manet progressed the Impressionist movement into Post-Impressionism, Seurat chose to take Impressionism and put his own twist on it. Which he did with great success.

Whilst the painting technique behind Pointillism, which sees individual dots of pure, unmixed colour individually applied to a canvas, is usually the key characteristic associated with the term,it is the scientific theory behind it that truly defines Pointillism (or Divisionism, but we will get to that in a moment!).

The Impressionists sought to literally paint their impression of the world in front of them onto canvas. Often working quickly en-plein-air (outside) in order to capture the light and colours of that fleeting moment. Seurat chose to take this artistic intention and adapt the method of doing so.

Instead of a rapid, expressive and subjective approach, Seurat attempted to capture light and colour through the use of optical theory. By pedantically placing brushstroke (either a short horizontal dab or a dot) next to endless other brushstrokes of pure primary colours, Seurat believed the spectator’s eye would do the mixing, as opposed to the palette.

Pointillism versus Divisionism

Georges Seurat, The Seine at La Grande Jatte, 1888, Oil on Canvas

Before we delve into the dazzling visual world of some of these pointillist works, we must first briefly address the issue of terminology.

It has been suggested that the word ‘Pointillism’ comes from an observation made by French art critic Felix Feneon, having once described the technique as peinture au point (“painting by dots”). Whilst another source claims he instead coined the term ‘Neo-Impressionism’.

Whichever one is correct, however, sources such as the Tate and The Met suggest that the term ‘Pointillism’ is incorrect when describing the work of Seurat and his followers, due to Seurat and Signac’s repudiation of the word. They suggest that Divisionism was their preferred term, which, really, means pretty much the same thing.

Despite all of this debate, given the way that art history has been documented in the last couple of hundred years, the contemporary understanding of Pointillism does seem to be one synonymous with Seurat and his work. It has been used by art historians from Gombrich, in his Story of Art, to the online glossary of The National Gallery and so, whether Signac or Seurat liked it or not, Pointillism has probably earned its place as a recognised name for the painting technique.

The Pointillist Manifesto

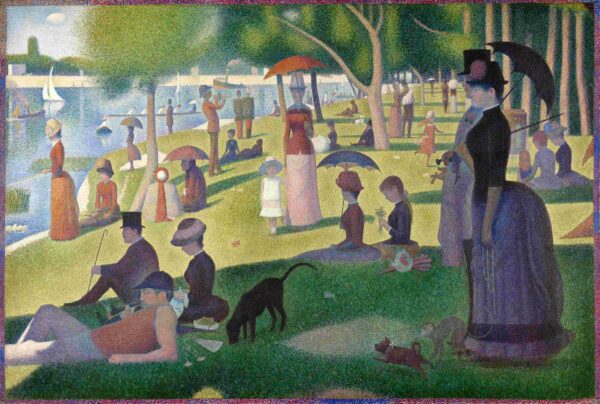

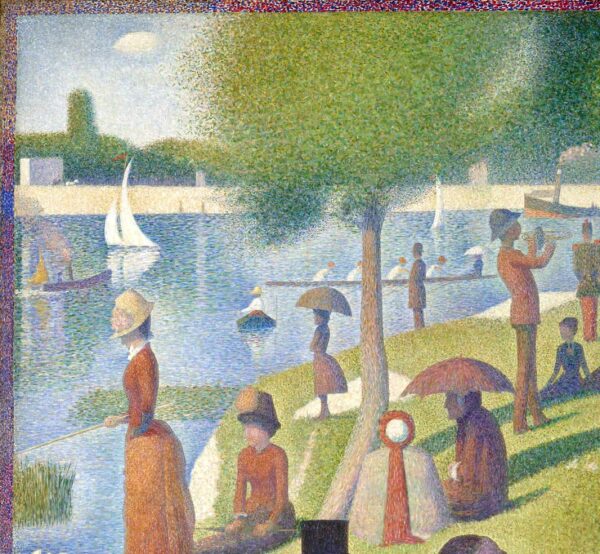

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,

Now comes the time to have a look at where our beloved colour blue plays a role in Pointillism.

Given the most common Impressionist subject matter was either scenes of everyday life (Genre scenes), imagery of landscapes and the outdoors, it was natural for that to continue in Seurat’s Neo-Impressionism. With the sea, rivers and the sky all being important parts of the harbour scenes, scenes of urban life and other depictions of nature that make up the Pointillist oeuvre.

Widely agreed to be his most famous work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-1886) is also recognised to be George Seurat’s visual Pointillist manifesto. The large painting depicts an array of social gatherings in tableaux upon the banks of the river Seine. Seurat had already been painting scenes of modern, urban life before creating this masterpiece, in which he references the compositions of Old Masters whilst commenting on social hierarchy and the context of the time in Paris.

Instead of capturing the dynamism and movement the Impressionists sought, Seurat’s systematic application of paint leads to a far more rigid portrayal of the human form. Something he wanted to achieve in order to pay homage to the timeless artwork of Egyptian friezes and Greek sculpture. The countless dots of paint demonstrate their purpose as they merge and create almost-solid areas of colour.

Blue in A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

Detail of the Seine in A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

Whilst the painting harbours deeper messages, colour theory was of first and foremost importance to Signac. Upon first glance, we can see how blue has played an important role in the piece’s palette. Firstly, the eye is drawn to the strong female in side-profile, whose outfit in varying deep blue tones. Her stance, her clothes and her exotic pet, captures the viewer’s attention and makes you wonder about her reason for being there.

As the eye follows the perspective of the composition back, it is the blue of the umbrella, hats and shadows that contrast the tones of orange in the work; exhibiting the utilisation of complementary colour theory. Finally, we reach the top left corner of the painting, where boats drift upon still, blue water. Here, Seurat successfully captures the light and its reflections through the use of his pure white dots, following the theory that optically mixed colours create greater luminosity.

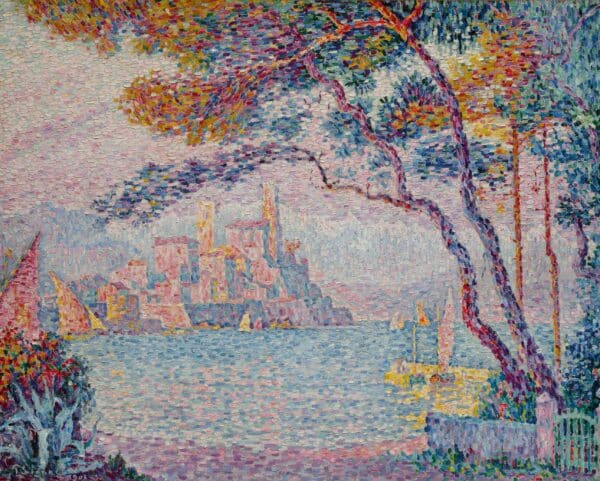

Whilst Pointillist works such as La Grand Jatte incorporate both the painting technique and Seurat’s commentary on modern life, there are other Pointillist works that are more simply portrayals of nature’s peace and serenity. For example in Seurat’s work The Seine at La Grande Jatte and Signac’s Antibe. Soir we can see tranquil blue waters and blueish pinkish skies convey the pure beauty of nature through their use of colour.

Pointillism and its Legacy

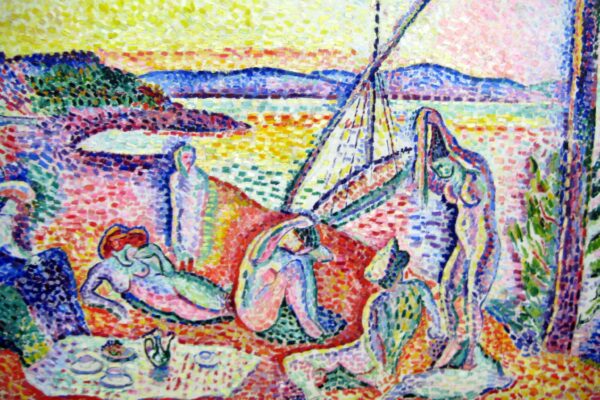

Henri Matisse, Luxe, Calme et Volupte, 1904, Oil on Canvas

Although Seurat’s life was tragically cut short due to illness, Signac and his other followers continued to advocate the Pointillist technique throughout their lives and work. We can see the influence of Seurat’s methodical dots in the work of Pissarro, Matisse and the Fauves, Van Gogh and even Kandinsky.

Here at Blue & White Company we celebrate the unique way in which the Pointillists thought about colour and hope that next time you see a dotty picture in the flesh you take a moment to let your eyes do the work, as Seurat hoped they would!

“The Painter must leave the beholder something to guess.”

E H Gombrich, Art Historian