‘Cobalt – a divine colour…for putting space around things’ Van Gogh

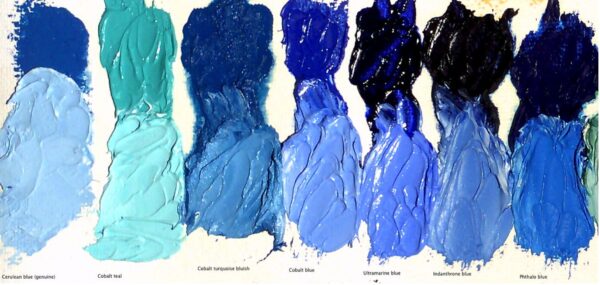

Modern oil paints by Williamsburg, from the left: Cerulean Blue (genuine), Cobalt Teal, Cobalt Turquoise Bluish, Cobalt Blue, Ultramarine Blue (synthetic), Indanthrone Blue, Phthalo Blue.

The metal cobalt has been used for centuries as an ingredient in glass making. It can be found in the luminous bright colours of medieval stained glass windows, as well as in the blue and white pottery of China produced during the Tang dynasty.

Then, in the nineteenth century, the pigment cobalt blue was produced by a distinguished chemist called Louis Jacques Thenard, who had been looking for a new blue. Thenard had been appointed by the French government to find a more affordable alternative to the more costly lapis lazuli pigment, also known as ultramarine blue.

Ultramarine was made from the crushed up semi-precious stone lapis, excavated from caves in Afghanistan. Cobalt blue, unlike ultramarine, was semi-opaque, pure and vibrant. It dried quickly and could be mixed with other colours easily. This discovery of a new blue, often referred to as ‘Thenard’s blue’, quickly caught the attention of artists all over the globe.

“The invention of cobalt blue allowed the explosion of bright colour and creativity that we see in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings,” said Dr. McKever, The Origin of Cobalt Blue

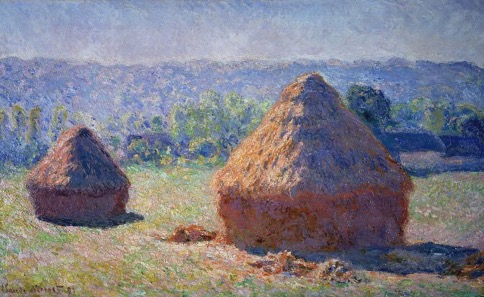

Haystacks, End of Summer’ by Claude Monet, 1891, oil on canvas. Monet is known to have used cobalt blue in his palette including in this painting.

One such painter who was keen to get his hands on this ‘new blue’ was Jean Auguste Renoir. Like so many other Impressionists, Renoir is known for his bohemian scenes of everyday life in Paris. Through X-ray imaging of his very blue work entitled ‘The Umbrellas’, it was discovered that he used cobalt blue predominantly at first and then later included much more ultramarine blue. The figures’ clothing on the right in the foreground exhibit cobalt blue shades compared to those on the left.

‘The Umbrellas’ by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, c.1880-1886. Oil on canvas.

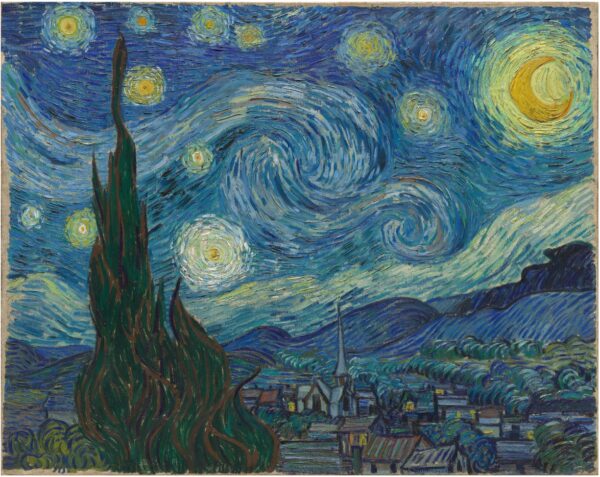

The Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh employed cobalt blue in many of his works. In June of 1889, he set out to paint his masterpiece ‘Starry Night’. He innovatively used a variety of blue pigments in this, and in his other works, in his brushstrokes which sit side by side. He used cobalt blue to represent the light emanating from the moon. In fact, he enthusiastically talks of cobalt blue in his letter to his brother Theo, who had sent him blue colours.

‘Cobalt — is a divine colour, and there’s nothing so fine as that for putting space around things’. Van Gogh’s letter to Theo

‘Starry Night’ by Vincent Van Gogh, 1889. Oil on canvas.

The fact that cobalt blue was used by artists only from the late nineteenth century led to an interesting story. Han Van Meegeren was a Dutch painter and is known now as ‘the most daring art forger of modern times’. In 1932, Van Meegern painted the biblical scene ‘Supper at Emmaus’, claiming it as a real painting by the Dutch master Vermeer. He fooled one of the most notorious art historians of the time, Abraham Bredius, and in 1937 Bredius declared the Van Meegeren to be ‘the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft’ in the art history journal The Burlington Magazine.

Van Meegern was so dedicated to seeking authenticity that he made sure to grind his pigments using the same techniques as Vermeer and even ‘baked his canvases to achieve a look that suggested centuries of cracking’, as noted in an article on his forgery more than fifty years later.

‘The Supper at Emmaus’ by Han van Meegeren, 1936–1937, oil on canvas

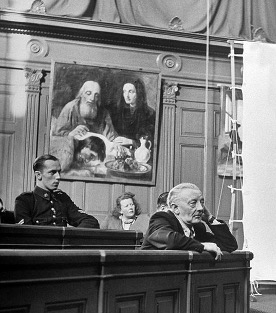

Van Meegeren painted another so-called Vermeer, titled ‘Christ with the Adulteress’. Hermann Göring bought this work in exchange for 200 paintings he had collected, deeming it to be the most treasured piece. However when World War II was over, allied forces recovered Göring’s art collection and returned it to its rightful owners. As Vermeer’s paintings were of national interest, a private sale to Nazi officials was considered treason. Van Meegeren appeared in court and confessed that he had indeed sold the painting to a Nazi banker, Alios Miedl originally, who had in turn sold it to Göring. Van Meegeren admitted that he had painted the image and had to prove it by producing a new painting to convince incredulous art history experts.

For the trial a scientific examination of the forged paintings was conducted. It was discovered that lapis lazuli and ultramarine were used in them as well as the more modern cobalt blue. However, this was an artificial pigment not manufactured until the nineteenth century. This provided key evidence that they were in fact forged, as Vermeer would not have had access to cobalt blue. The case was closed, Van Meegern was found guilty in 1947 and later died of a heart attack.

Han Van Meegeren in trial 12 November 1947