All in the Name…

Indigofera tinctoria plant genus in bloom

Indigo is one of the oldest textile dyes, believed to have been used more than any other dye throughout history. It comes from a large genus of about seven hundred species of tropical herbs and flowering plants that principally thrive in tropical and arid zones of the world. Many different cultures over time have learned the secret of extracting the colour from these plants.

The reason why such an assortment of exuberant blues can be produced is mainly due to the fact that natural indigo can be extracted from a vast variety of plant leaves. For instance, during the Medieval period the plant woad became an important dyeing agent for the British for obtaining indigo. Barbara Brackman, in her book Making History – Quilts & Fabric From 1890-1970, suggests that the best source is a plant called Indigofera tinctoria or known more commonly as true indigo.

In the eighteen century, European dyers distinguished between thirteen different shades of indigo that were in regular use. Jenny Balfour-Paul, the artist and lecturer who has researched indigo for more than two decades references in her book, Indigo, the names created by these dyers. From the lightest first, these were: ‘milk-blue, pearl-blue, pale-blue, flat-blue, middling-blue, sky-blue, queen’s-blue (royal), Turkish-blue, watchet-blue, garter-blue, mazareen-blue, deep-blue and infernal or navy-blue’. Additionally, each individual will have their own way of seeing and naming different blue shades, informed by their personal associations.

We’ve adopted the 18th century name, pearl blue, for one of our luxury cashmere throws as, for us, it seems to capture the gentle essence of its colour…

Pearl blue diamond cashmere throw, Blue & White Company

The dying process is still fascinating and magical to this day, which continues every day in many parts of the world. The dye is extracted from one of these plants through fermentation and then is dried into cakes that can be transported and traded.

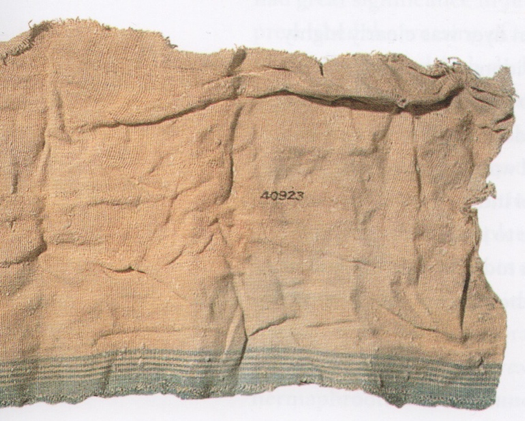

From archaeological excavation, we can see that indigo was already in use by 3000 BC, perhaps even earlier. In the Ancient world it was used for several purposes. This powerful dark blue carries with it historical associations of affluence and majesty, and was often embedded in the textiles of the nobility. It was important too in the use of Egyptian cloths. Their woven textiles were highly regarded at the time and Jenny Balfour-Paul’s research has shown that indigo dye can be seen on the borders of mummy cloths in which they would have woven dyed threads into linen using a loom. This multipurpose dye was also noted for its medicinal and antiseptic properties in ancient civilisations.

Textile fragment from Deir el-Bahri, Upper Egypt, with indigo-dyed stripes. Eleventh dynasty (c.2000 BC)

In some countries indigo is seen as having a spiritual significance and thought of as very individual compared to other dyestuffs.

Between 1815-1848 the world was changing. The Industrial Revolution fuelled the creation of a modern capitalist system, alongside it providing an economic boost in trade. Whilst JMW Turner was painting the arrival of new steam engines in The Fighting Temeraire (1839), it was discovered that indigo crop could be grown in abundance and it became much more valuable than any other dyestuffs. Large plantations were primarily established in Central America and South America and trade production increased speedily. The sheer labour that went into farming it on such a massive scale cannot be underestimated, which lends a significance to the way we might appreciate indigo today, thinking of the centuries of learned skill and care that was involved.

Indigo became more accessible to everyone due to its mass trading, and eventually it was available for everyday uses. This was also due to the fact that a synthetic indigo dye was successfully invented, propelled by the work of a German chemist called Adolf von Baeyer in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Thus indigo, which was normally reserved for luxury textiles, developed into commercial production. The majority of indigo prints we see on designs within fashion today will be made of synthetic dye. Nevertheless, indigo remains a treasured dye, the process infused with a long and respected history of labour and craft, which is also unique in creating an eclectic nuance of shades.

To many people, the combination of indigo and white has a timeless freshness that lasts from summer to winter.