Defining Techniques: The History of Impasto

Impasto in a detail of Van Gogh’s Wheat Field with Cypresses

Over the course of art history, we have seen the rise and fall in favoured styles, subject matter and techniques. One particular technique, however, has only increased in popularity as time has gone by. This technique is known as impasto.

Meaning ‘mixture’ or ‘dough’ in Italian, impasto describes a way in which an artist applies paint to canvas and has the ability to move an artwork from sensuous to dramatic. Given the significance of impasto over the centuries, we thought we would explore its history and why it remains a core method used by artists today.

Achieved via the use of brushes, palette knives and even the artists’ own hands, impasto typically refers to the heavy layering of oil paint to a work’s surface. It can influence the lighting, dimensionality and expressive qualities of a painting, and artists have often adapted the technique to fit their own personal style.

The easiest way one might identify impasto would be to look at a piece side-on and judge whether or not the medium is projecting from the canvas. However, as we will learn by looking at the origins of the technique, it is both more complex and intriguing, than that. Although, fundamentally, impasto relates to the creation of texture, it hails from a period where the desire to capture energy and dynamism in art had begun to challenge more linear practices.

The Origins of Impasto

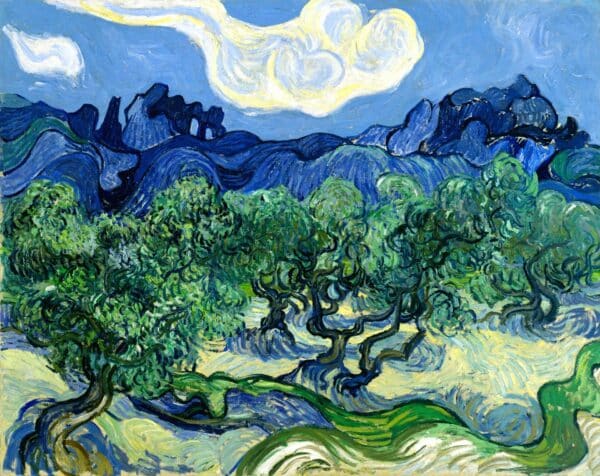

Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Today, those familiar with art history may immediately associate impasto with the work of artists such as Van Gogh, Jackson Pollock and Frank Aurbach. And rightfully so. The way in which these masters employed the technique could sometimes be considered extreme. The textural presence of impasto frequently being unmissable in their work. However, impasto can very much be spotted in paintings created far earlier than those of these modern masters.

In fact, artists active as early as the 16th century are often credited with the initial development of impasto. Since this method of handling paint has been so significant we thought we would take a brief look at the origins of impasto in western art history. Let’s dip into its evolution and explore how it has culminated in the fantastically striking form that is now almost entirely synonymous with Modernism.

Impasto in the Art of the Venetian Renaissance

Titian, The Flaying of Marsyas, c.1570s, Oil on Canvas

When debating the first known users of impasto in art history, Titian and Tintoretto are the most unanimously agreed upon. Two of the major artists of the Venetian Renaissance, between them these Italian masters created many iconic, colour rich and vividly tactile works that could now be seen as the catalyst for the future of impasto.

It may seem slightly surprising to some, when comparing Titian’s work to the work of an artist like Auerbach for example, but, actually, Titian’s loose brushstrokes and freer application of paint are some of his most renowned qualities, as with Auerbach. It is arguable that Titian’s innovative style was an intentional move in the opposite direction of sfumato (a stereotypical renaissance painting technique that blurred the transition between tone and colour using imperceptible brushstrokes) and instead towards the impasto technique we know today.

Demonstrated in a number of his works, Titian’s early use of impasto can be seen in paintings such as The Flaying of Marsyas and Diana and Callisto. Each of which is the depiction of a dramatic narrative that Titian captures through his energetic brushstrokes and generously layered oil paint. His technique creates a near-tangible texture which, in turn, animates the folds in the rich textiles and the swirling clouds in the turbulent skies.

Through his use of impasto, Titian remains both true to his material (oil paint) whilst simultaneously heightening the dynamism of each composition.

Tintoretto, Miracle of the Slave, 1547–1548

Similar observations can be made about Tintoretto’s work. This is understandable given the close proximity and timeframe in which he lived to Titian. In paintings such as Susannah and the Elders and Miracle of the Slave, Tintoretto’s rapid painting style (which may have been a direct influence of Titian) combined with the layers of oil is equally indicative of the early impasto technique.

Impasto Outside of Venice

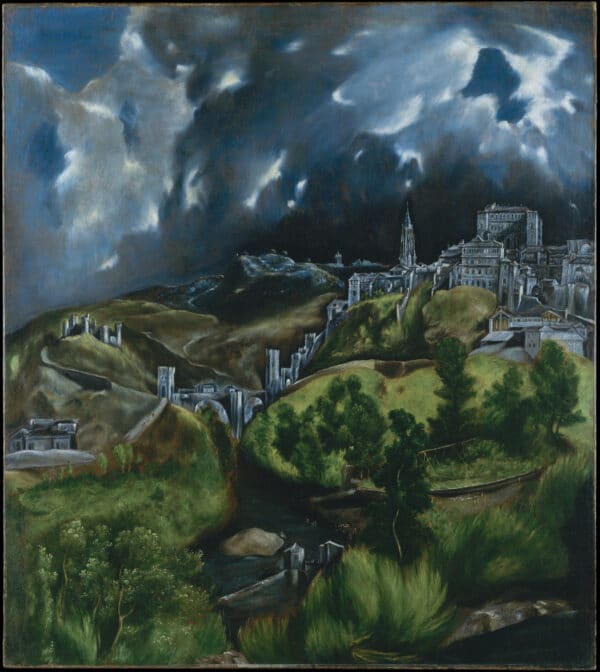

El Greco, View of Toledo, c. 1599–1600, Oil on Canvas

Popularised by the Venetian masters, impasto in its early form was appearing more regularly in paintings by the end of the 16th century and throughout the 17th. As more artists from across Europe, travelled to Italy to train and to study, the technique began to spread throughout the Western art world.

Late Renaissance and Baroque painters such as Velaszquez and El Greco in Spain, Carravaggio in Rome and Rubens and Rembrandt in Holland are just some of the masters in whose work we can see prime examples of gestural brushwork and pastose surfaces.

That being said, whilst impasto can be recognised in the telling texture of layered paint in El Greco’s atmospheric, thundery blue sky above Toledo or as one of Rembrandt most notable painterly attributes, the use of impasto didn’t truly hit its stride until the 1800s.

Impasto and Modernism

El Greco, View of Toledo, c. 1599–1600, Oil on Canvas

The 19th century brought a significant shift in Western painting styles. Art history saw the beginnings of modern art and a multitude of avant garde movements spring up in swift succession. Though many artists remained loyal to the academic school, artists such as Gustav Courbet and Claude Monet counteracted tradition with stylised realism and captivating impressionism. For both of these styles impasto is perfectly suited.

As we previously mentioned, impasto is now pretty much synonymous with these avant garde movements, given the technique is so aligned with the aims of the movements themselves.

For example, in Monet’s work, impasto often changes the way light reflects on the canvas and, therefore, its overall appearance. This in itself could be seen as a parallel between the technique and the focal role light played in the Impressionist manifesto. Then we have Van Gogh, who used impasto to express passion and emotion, whilst the work of Frank Auerbach and Jackson Pollock’s use of it challenged the boundaries of handling oil paint.

Tactile Home Touches

Impasto can be found in so many works of textural delight throughout art history and, like with many things, it appears we have Titian (and Tintoretto) to thank for it.

The tactile nature of impasto is incredibly appealing and, as many designers have shared, texture can provide a wonderful effect when it comes to interior design as well. If you are interested in the joys texture can bring when decorating and styling your home, we hope you might love our beautiful blue and white mosaic vases as seen below and our fun and stylish handcrafted porcelain ceramic shakers.