The Blue of Vermeer…

The Girl with a Pearl Earring, Vermeer (1665) oil on canvas. In Mauritshuis in The Hague.

The much loved seventeenth century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer remains something of an enigma, even today. After his death in 1675, unlike many artists, Vermeer did not leave behind any drawings or plans of his paintings, nor any diaries. Yet we have come to recognise and relish the idyllic quality that Vermeer captures in his work, an overall sense of tranquillity and calm, that some believe surpasses that of his contemporaries. It is very possible that this sense of serenity is partly produced by the artist’s avid use of ultramarine blue. The quality of this blue is all in the name, ‘ultramarine’ translating to ‘beyond the sea’. It was a superior blue to any other as it was extracted from the expensive, rare and deep lapis lazuli semi-precious stone, originally discovered by the Egyptians from mines in the Middle East. Other artists of the time would have used a relatively small amount of ultramarine – or used a cheaper alternative, a less impressive blue made from copper azurite – but Vermeer added this wonderful and distinctive blue to many of his paintings of domestic scenes.

In perhaps his most renowned but equally elusive painting The Girl with a Pearl Earring, Vermeer chooses a bold and strong consistency of ultramarine blue, coupled with yellow ochre for the headdress, a key feature in the work. The way her head is turned with her direct, unfaltering gaze suggests that she might have known the painter. This in turn causes us as viewers to engage with the painting in a more intimate way. It has been speculated that the sitter for this portrait may have been one of Vermeer’s maids. This was later reinforced by Tracy Chevalier’s novel Girl with a Pearl Earring and the later 2003 film adaption with Scarlett Johansson who plays this imaginary maid called Griet. Some art historians think the sitter may be one of Vermeer’s daughters who would have been a teenager at the time. Her true identity is left unknown…

Scarlett Johansson as the fictional maid Griet and Colin Firth as Johannes Vermeer in the Girl with a Pearl Earring 2003 film, directed by Peter Webber.

Despite his still limited palette, Vermeer’s combination of vivacious blue and yellow hues draws our attention closer. The young girl emerges out of the darkness with a sense of ethereality, combined with a bold directness. It appears as if the end of her yellow headdress has been dipped in ultramarine paint, lending it a delicacy as though it were a refined border. This effect may well have been produced by Vermeer painting a layer of ultramarine as glazed over the yellow ochre of the fabric. This delicacy is further subtly emphasised by very small dots of colour suggesting a shimmering quality to her headdress.

In previous centuries, before Vermeer’s time, ultramarine would have been reserved for use on painterly representations of Christ or the Virgin Mary due to its preciousness. It then started to be used more freely by artists who could afford it. It is clear Vermeer cherished this blue and the effects it could lend to a painting, as he made great use of it despite his straitened circumstances and its costly price. The artist would most likely have been aware of the history of lapis lazuli (from which ultramarine is ground from) and thus perhaps hoping to align the girl here with a historic, yet timeless otherworldliness through his lavish use of blue.

Once the painting was bequeathed to the art museum Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Dutch painter Jan Veth said of it, in the early twentieth century: ‘more than with any other Vermeer one could say that it looks as if it were blended from the dust of crushed pearls’.

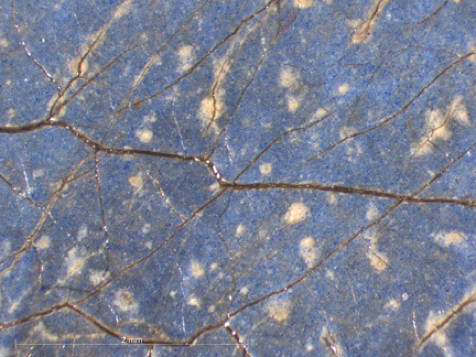

Photomicrograph showing deteriorated ultramarine paint of the chair detail painted in Vermeer’s Young Woman Standing at a Virginal (c.1670-2). National Gallery, London.

In the 1600s, artists had a limited amount of pigments at their disposal which they would grind up themselves. In this way, the roles of alchemist and artist were more closely intertwined, much more so than our effortless access to synthetic paints today. Vermeer therefore would have created his own spectrum of nuanced blue hues by experimenting in combining it with other pigments.

There is an intimacy to Vermeer’s paintings which is due to many factors including his colour palette, their small scale, the informality of the compositions as well as the absorption of each figure in their silent activity in which the viewer themselves becomes absorbed in watching. An image primarily composed of blue and yellow, The Lacemaker is meticulous with her delicate work. Bent over on a table, she concentrates purely on this one activity, making lace. We as viewers are given the opportunity to watch this closely too.

The Lacemaker, Vermeer (1670) oil on canvas. The Louvre, Paris.

Although only a painting, there is a feeling of movement; as if her fingers are slightly, softly moving to and fro, in accordance with the bobbins and pins she uses whilst she works. Despite it seeming like an everyday task, displayed is a wonderful sense of devoted artistic ability and skill in both the lacemaker and the artist for painting it. This concentration on craft and the love of making is very important and valuable to us at the Blue & White Company too…